Everything You Need To Know About Gujarat’s Textile Heritage: Mashroo And Bandhani

Jul 20, 2024 | Shagun Sneha

Gujarat holds a rich textile heritage that spans centuries. It is renowned globally for its vibrant fabrics, intricate embroidery, and traditional craftsmanship. The textile heritage of Gujarat is a colourful tapestry of skill, culture, and history, deeply woven into the fabric of its society and revered worldwide for its beauty and craftsmanship. A considerable portion of India's textile production originates in Gujarat, a place where a rich tradition of craftsmanship thrives.

Gujarat holds a rich textile heritage that spans centuries. It is renowned globally for its vibrant fabrics, intricate embroidery, and traditional craftsmanship. The textile heritage of Gujarat is a colourful tapestry of skill, culture, and history, deeply woven into the fabric of its society and revered worldwide for its beauty and craftsmanship. A considerable portion of India's textile production originates in Gujarat, a place where a rich tradition of craftsmanship thrives. Introduction:

Bhuj holds significant importance in Gujarat's rich textile heritage because of its role as a hub for traditional craftsmanship, particularly in the Kutch region. It is greatly renowned for its production and showcasing of diverse textile arts such as bandhani (tie-dye), intricate embroidery, Rogan art (a unique form of fabric painting), and skilled leatherwork. The town's 'Bhuj Haat' near Jubilee Ground serves as a marketplace where local artisans from surrounding villages gather to sell their handmade textiles, thereby preserving and promoting the textile heritage of Gujarat.Top of Form

Mashroo:

Let’s know about the history of Mashroo

Mashroo, originating from an Arabic term meaning "permitted," emerged in response to Islamic laws prohibiting the use of pure silk due to its animal origin. This unique fabric combines a silk outer surface with a cotton inner side, allowing it to adhere to religious guidelines while providing a luxurious appearance. Introduced possibly from the Ottoman Empire to India in the 16th century, mashroo found fertile ground in Gujarat, where Akbar brought skilled weavers to his royal workshops in 1572. This exchange of expertise between local and foreign artisans enriched Indian textile production, spreading mashroo weaving to centers like Lucknow, Daryabad, and Samna.

Historically, mashroo thrived in various regions including Uttar Pradesh, Sindh, Bengal, and Tamil Nadu, known for producing distinctive varieties like sangi, galta, and gulbadan. However, its production dwindled in the late 19th century, currently surviving in limited quantities in Patan and Mandvi, Gujarat, and in Andhra Pradesh under the name kutni.

The legacy of mashroo weaving is attributed to families like the Mamtora community, who brought their weaving knowledge from the West and impart it to local artisans, thus sustaining the craft's tradition across generations. This cultural exchange not only preserved religious sensibilities but also enriched India's textile heritage with a blend of technical skill and artistic expression.

The start of the use of Mashroo

Mashroo is a hand-loom woven fabric distinguished by a silk warp and cotton weft, traditionally embellished with vibrant striped patterns created from dyed yarn. While originally synonymous with silk and cotton blends, modern variations often substitute silk entirely with cotton or cotton blends. The sateen weave, characterized by a slight glossy sheen, mimics the appearance of pure silk, making mashroo a preferred choice despite its narrower width of 22 inches, with some weavers expanding to 36 inches to accommodate garment requirements like ghaghras (skirts) and cholis (blouses), which typically need widths of 32 inches and 21 inches respectively.

Primarily embraced by various communities such as Ahir, Rabari, Marwada, Chayand, and Muslims, mashroo holds cultural significance, especially in the celebrations and traditional attire like wedding garments.

The fabric's diminished presence underscores the challenges facing its survival in contemporary markets, a poignant contrast to its historical prominence and widespread cultural significance.

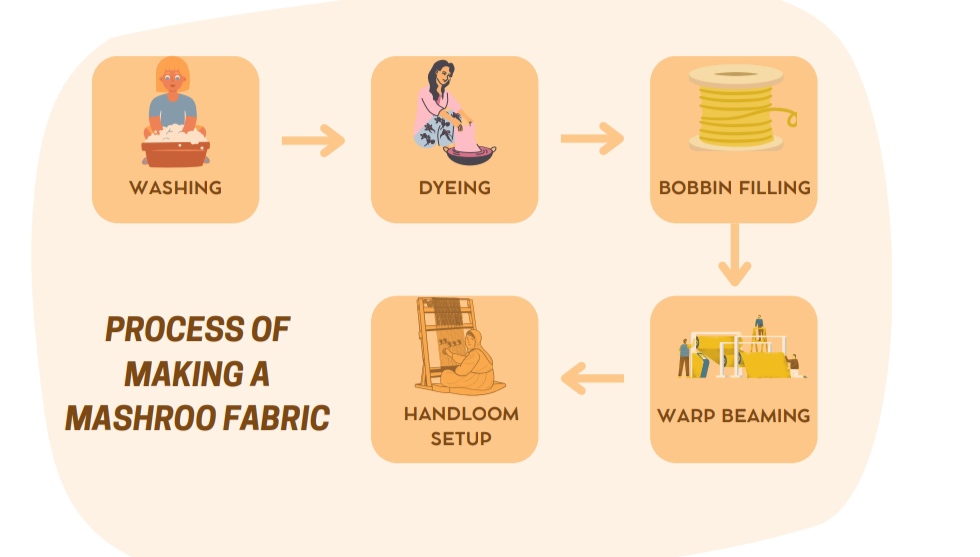

What is the process of making mashroo fabric?

· RAW MATERIALS FOR MASHROO:

Cotton and silk hanks

Angoriya (fruit)

For dyeing:

Natural dyes

Harde (for light brown colour)

Pomegranate peels (for pink)

Indigo (for blue)

Tobacco (for black)

Reactive dyes

Synthetic dyes

Tamarind and Salt for colour fixation

· ELEMENTS OF THE HANDLOOM:

Tanjini (stick used for warping)

Tor (winding log for mashroo fabric)

Nado (shuttle)

Nada (bobbin)

Hatha

Jaala

Fanni (made of sweet water grass)

Pagada (peddles used for weaving designs)

Nakas and lassa (parts of pagada)

Racch (group of taaki)

Taaki

Kaana (stick used in making for taaki)

Drum (winding log for the yarns)

Patli or Gutka (stops the shuttle on both sides and bounces it back)

Guthiya (handle for moving the shuttle through the warps)

Padang (stick used to keep the weaved fabric in its original dimensions)

Wadar (rope used to rotate the drum during weaving)

· TOOLS USED FOR MASHROO:

Tanjini (stick used for warping)

Adand (frame for warping)

1. Washing:

Before any processing begins, it is vital to thoroughly cleanse the hanks of kora yarn (untreated yarn) to remove any impurities. Upon purchase, this yarn undergoes a washing process, where some weavers use a local fruit known as aangoria for its natural soapy properties. Resembling a shriveled lemon, the fruit is peeled and soaked in water overnight. It is then boiled until it dissolves into a thick, soapy solution. To prepare the yarn for dyeing, this solution is then diluted with water in a specific ratio depending on the amount of yarn to be processed. The yarn is immersed in this solution for several hours, allowing the soapy mixture to cleanse it thoroughly. Afterward, the yarn is gently rinsed by hand to remove any residue and then left to dry naturally.

2. Dyeing:

Currently, reactive dyes are highly favoured by weavers, as mercerized cotton is preferred over silk or rayon cotton. The shade matching of the yarn is done visually, a skill developed through years of practice by weavers. The dye bath is prepared and heated. Separately, a dye liquor solution is made by adding 2 to 3 spoons of dye to a glass of water, depending on the desired shade. Once the water bath temperature reaches between 40 and 60 degrees Celsius, the dye liquor solution is then added and mixed thoroughly until the water reaches boiling temperature, with constant stirring. The yarn hank is held by two rods (metal or wooden) at each end and continuously dipped into the dye bath. Vigorous agitation is applied until the dye bath reaches saturation. A couple of spoons of common salt are added to regulate the dye uptake, preventing uneven dyeing by controlling the colour transfer from the dye bath to the yarn. The hank is dipped again in the dye bath, coupled with stirring. Once the dye bath is exhausted, the hank is left to dry.

3. Bobbin Filling:

This step is typically performed by the women in households. Bobbin filling can occur simultaneously with the other handloom processes, ensuring continuous production. The yarn is wound using a spinning wheel (charkha). The hank is placed on top of a hexagonal spinning top, which is aligned parallel. The thread from the spinning top is threaded through the spinning wheel. By turning the spinning wheel manually, the yarn is transferred to small bobbins. These bobbins serve as weft yarns which are placed inside the shuttles used during weaving.

4. Warp Beaming:

It is a complex and intricate process that requires careful calculation. Proper dyeing is essential to create the design. Warping drums are typically used for this step, though weavers sometimes innovate using other work aids. The hanks are transferred to creels in a process similar to bobbin filling. The creels are then used to create long loops of yarn on the warping drums, although the warping drums restrict the colour options.

5. Handloom setup:

The handloom or the Godasar setup involves connecting each part of the loom with thin ropes to integrate them. The heddles are connected together, with seven heddles corresponding to seven pedals. The jaaro ensures synchronized movements of the pedals and heddles, with each responding to the assigned pedal. The tying is done so that the pulley is activated each time a pedal is pressed. The dora, (thread), is tied to the warp threads. A 22-inch wide mashroo fabric uses 28 hanks, each containing 70 threads. The elements of the handloom are as follows:

Godasar- frame loom

Gakdaasar- pit loom

Heddle- Frame

Rach- the hudlle

Kana- shafts

Pagda- peddle

Garodi- pulley

Jaaro- thread tyed to the peddle

Padang- a metal rod used to set the width of the fabric

while weaving.

Naado- shuttle

Tor- winding log for the woven fabric

Toffani- the handle on the tor

Bannini- collective tied threads of the rach

Favourable factors that increased the popularity of Mashroo

Mashroo, having the width of only 18 inches, had limited use in the textile industry. The narrower width meant it couldn't be used for making a variety of extravagant and voluminous garments. The primary consumers were the Ahir, Rabari, Patel, Muslim, and Meghwal communities, along with its extensive use by royals. Mashroo was considered very auspicious and was used majorly in ceremonial textiles.

About twenty-five years ago, an undocumented gentleman set up a stall at an exhibition of mashroo textile in Mumbai, which showcased the fabric. This contributed to its success and increased popularity. Mashroo reached its peak success during and after the mid-1980s, immensely influenced by Bollywood.

Non-favourable factors

The sharp decline in the demand for mashroo led to its disappearance from the market. One major shortcoming was its width; at only 18 inches, it offered very limited options for garment construction. Additionally, the colour scheme, with many bright hues, was often too intense, even for a country with a rich colour palette like ours. The traditional mashroo colours, especially the paanch pattu, could be irritating to the eye.

In the 1990s, aiming to increase profits, the weavers decided to produce and dye the fabric themselves. This led to extremely poor production quality, which diminished its market value. Consequently, the people stopped buying it, further contributing to its poor marketing.

Sundarii Handmade thechakorshop Urban enjoy

Bandhani:

Let’s know the history of Bandhani

Tie-dye, a resist-dyeing technique where the fabric is tied or folded to resist dye in certain areas, has ancient roots across various cultures. Its history spans various continents, with notable traditions in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The patterns and the methods have evolved over centuries, reflecting the local customs, resources, and aesthetics. Bandhani is one of the oldest forms of tie-dyeing, originating in the Indian subcontinent, particularly in Gujarat, Rajasthan, Sindh (Pakistan), and parts of Uttar Pradesh. Historical references suggest its use in the Ajanta Caves, dating back to the 6th century. Bandhani is deeply rooted in the Indian culture and is often used in traditional garments such as sarees, dupattas, and turbans. It is associated with various life events, including weddings and festivals, symbolizing auspiciousness and prosperity.

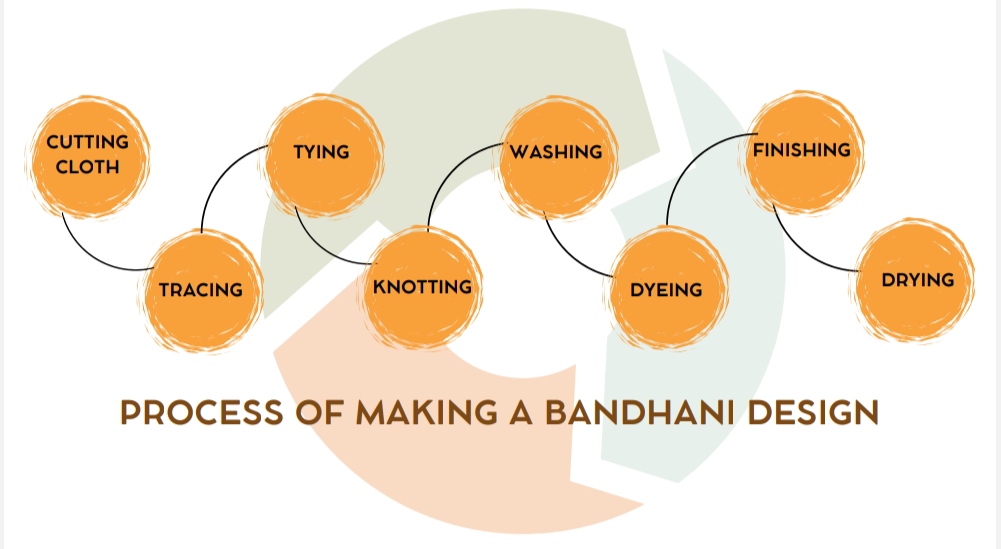

What is the process of making a Bandhani design?

· RAW MATERIALS FOR BANDHANI:

Fabrics: Cotton, Silk, Wool, Synthetic Textiles, Malmal, Georgette, Artificial Silk

Cotton Threads

Wooden Blocks

Farma (transparent plastic sheet which bears design created by small pin holes)

Mixture of burnt sienna and water for printing of design

Bleach

Dyes: Natural Dyes, Direct Dyes, Reactive Dyes, Vat Dyes, Acid Dyes

Sodium hydrosulphite for discharge

Polythene and plastic threads (for colouring bandhej)

For colouring: colour, alum, sodium, sulphate sodium, acid

· TOOLS USED FOR BANDHANI:

Wooden rods

Plastic tub

Hair Dryer

Plastic bags

Rubber bands

Sieve

1. Cutting Cloth: The process begins with selecting the appropriate fabric, typically natural fibres like silk or cotton. The fabric is then cut into the desired size, suitable for making sarees, dupattas, and various other garments.

2. Tracing: Designs are then traced on the fabric using washable inks or chalk. Traditional patterns often include dots, waves, and motifs. The tracing serves as a guide for where the fabric will be tied to create the resist patterns.

3. Tying: Following the traced designs, small sections of the fabric are tightly tied with threads. These tied portions will resist the dye, creating the distinctive patterns. The tying process requires precision and skill, as the tightness and placement of the ties has a direct impact on the final design.

4. Knotting: In Bandhani, the tied sections are often knotted multiple times to ensure that they remain secure during the dyeing process. Knotting helps in creating varied patterns and complex designs.

5. Washing: The tied fabric is washed to remove any impurities and also to ensure that the dye adheres evenly. This step also helps in setting the ties firmly in place.

6. Dyeing: The washed and tied fabric is immersed in dye baths. Traditional Bandhani dyeing uses natural dyes, although synthetic dyes are also common. The fabric may go through multiple dyeing stages, starting with lighter colours and progressing to darker shades. Each dyeing session is followed by re-tying different sections to create complex, multi-coloured designs.

7. Finishing: After dyeing, the fabric is untied. The threads are removed to reveal the patterns. The fabric is then washed again to remove excess dye and any remnants of the tying threads.

8. Drying: The finished fabric is spread out to dry, typically in shaded areas to prevent the colours from fading. Proper drying ensures the fabric sets well and the colours remain vibrant.

What are the business prospects of Mashroo and Bandhani in the global market?

The scope of international business for Mashroo and Bandhani is substantial, driven by the growing appreciation for unique and handcrafted textiles. These traditional fabrics can be leveraged in fashion and home decor, catering to consumers who seek exclusive, culturally rich products. There is a potential for high demand in ethnic wear, fusion fashion, luxury furnishings, and accessories, appealing to diverse tastes. Additionally, due to the increasing demand for sustainable products, ethical fashion through eco-friendly practices and fair trade can attract conscientious consumers worldwide. Export opportunities and cultural tourism can further enhance the scope of market reach, making Mashroo and Bandhani viable and lucrative ventures in the global market.

Information taken from Sutradhar (saptrang soot ke dhomil rang)

Recommended