The Handloom Heritage Of India

Feb 02, 2024 | Amisha

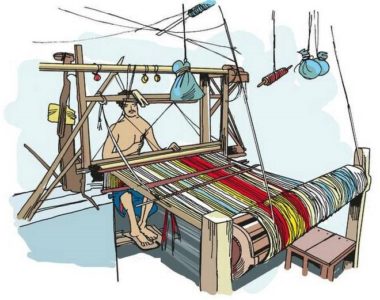

Indian hand-woven fabrics have a long-standing history and involve a significant number of artisans, particularly women and those from disadvantaged groups. The industry benefits from cheap labour, local resources, low investment, and a unique craftsmanship which makes it very sustainable and is increasingly valued by international consumers. However, despite these strengths, the industry contributes only a small portion to Indian exports. Therefore, there is a need to promote and harness the potential of this industry.

Indian hand-woven fabrics have a long-standing history and involve a significant number of artisans, particularly women and those from disadvantaged groups. The industry benefits from cheap labour, local resources, low investment, and a unique craftsmanship which makes it very sustainable and is increasingly valued by international consumers. However, despite these strengths, the industry contributes only a small portion to Indian exports. Therefore, there is a need to promote and harness the potential of this industry.

KHADI

Khadi fabric is crafted through the intricate process of spinning fibres such as cotton, silk, or wool into yarn using a traditional charkha spinning wheel. This yarn is then skillfully woven by hand on a loom, producing a fabric that possesses exceptional strength, durability, and a singular texture. The manual techniques employed in the hand-spinning and hand-weaving stages imbue Khadi with its distinct charm, characterised by its rough yet authentic appearance, which is highly cherished by individuals seeking natural beauty.

Khadi's exceptional attribute lies in its remarkable versatility. This textile can be skillfully intertwined in various weights and textures, catering to an extensive array of apparel and home decor options. From shirts, dresses, jackets, saris, and dhotis to bed covers and towels, Khadi effortlessly adapts to different purposes. Furthermore, its breathable and absorbent nature makes it the perfect choice for regions characterized by hot and humid climates. Moreover, Khadi's dyeability allows for an extensive spectrum of colors and designs to be seamlessly infused into the fabric.

One of the key attractions of Khadi is its focus on sustainability. The manufacturing process of Khadi is environmentally friendly because it avoids mass production methods and synthetic dyes, resulting in a smaller ecological impact compared to other textile production methods. The fabric is created using traditional techniques that do not rely on machinery or electricity, thereby reducing the carbon footprint of the production process. Furthermore, natural dyes derived from leaves, roots, and bark are used, minimizing the usage of harmful chemicals commonly found in the production of other fabrics.The manufacturing of Khadi in India not only creates job opportunities for rural communities but also plays a vital role in preserving traditional hand-spinning and weaving techniques. Additionally, it contributes to the economic growth of rural areas. This allows young individuals to make sustainable and ethical fashion choices while supporting fair trade practices.

Kanjeevaram Saree

Kanjeevaram, a town in Tamil Nadu known worldwide for its magnificent silk fabrics, is deeply rooted in a long-standing textile legacy that spans many centuries. The name of this technique originates from the Tamil words 'Kanji,' which signifies temple, and 'Varam,' which conveys the idea of grandeur. This highlights the town's sacred weaving heritage.

Kanjeevarams, made with the finest silk threads from mulberry trees, provide a lavish and fluid drape that is comparable to water. One of their most notable features is the intricate designs created from vibrant colors intricately woven together with the captivating allure of golden zari.

The intricate patterns found in the fabric capture the essence of royal tales, temple design, and the beauty of nature. Each unique design, including exotic flowers, ornate temple architecture, and detailed check patterns, showcases the skill and artistry of the talented weavers who conceived them. The renowned "Temple Border" designs specifically pay tribute to the towering gopuram structures of the shrines. Additionally, the check patterns known as kuyilkkombu delicately mimic the intricate lattice work seen on the windows of temple ceilings.

The renowned Korvai technique acts as the foundation, characterized by its intricate and interconnected weft patterns. Artisans employ a method similar to playing a veena, simultaneously manipulating multiple individual threads to produce these patterns. Experts weave the Pallu, the ornate border, and the saree body as separate panels. The last stage entails meticulous hand-stitching to seamlessly merge these components into a sublime six-yard fabric.

Paithani Saree

In the quaint town of Paithan situated along the banks of the gently flowing Godavari, a legacy of luxurious silks has blossomed over centuries. It was here that the Paithani saree was birthed - an epitome of Maharashtrian textile opulence that continues to enchant modern heirloom lovers. Crafted from the finest silver-dipped zari and pure mulberry silk yarns, the molten sheen of a Paithani immediately evokes affluence. However, the true mastery lies in its painstaking handwoven tapestry technique passed down generations. Dexterous weavers individually manipulate countless silk threads to transform them into motifs as resplendent as the Peacock Throne.

One of the most sought-after motifs from the Peshwa era remains the Hans or swan design showcasing a pair of intertwined swans against an ornate background. Believed to represent eternal love, these saris are highly coveted by brides. Equally opulent is the Ashrafi design inspired by broad-based gold coins. Lotus buds chain-stitched along the Pallu and borders further heighten its majesty. The timeless appeal of these decadent design tabloids project the Paithani as true sartorial heirlooms.

The painstakingly detailed crafting procedure explains the reverence these saris command as veritable textile treasures. It starts with dyeing silk yarns in brilliant hues using vegetable extracts. Then begins the laborious weaving phase sprawling over months where motifs are laboriously materialized on looms. Three highly skilled artisans work in tandem to create these textile masterpieces - the designer, weaver and zari artisan.

The enduring popularity of Paithanis over 200 years sets them apart as 'Queen of all Sarees' for their matchless opulence. Many a dynasty has coveted these silken splendours including the Peshwas, Scindias and Nizams. Today, Paithani sarees remain every Indian bride's ultimate wedding trousseau fantasy. Their luxe fabrication, heirloom value and sheer exclusivity perpetuate their significance as living legacies of India's rich textile heritage.

Kullu Shawls

Nestled in the winter wonderland of Himachal's Kullu valley, a vibrant tradition of wool weaving has blossomed over the years. The Kullu shawl and its close cousin the Chamba rumal stand testament to the unparalleled artistry of the region's skilled weavers.

Prized for their vibrant hues and intriguing patterns, traditional Kullu shawls play muse to the valley's charming scenery. Blooming floral motifs replicate alpine flora, while geometric designs take inspiration from local temple architecture. Despite the seemingly simple visual construct, the 3-4 ft shawls require immense precision and perseverance to produce. Only supremely skilled hands transform sheep wool into these wearable delights.

The wool base introduces incredible diversity - from the ultra-fine 16 micron Merino wool and the fluffy, soft Pashmina to sturdy fibres shorn from local Pattu sheep. Vegetable dyes create a rich colour palette of crimson, lapis blue and merigold mimicking wild Himalayan flowers. Uniquely, both sides of Kullu shawls display intricate designs created by the double-sided tapestry technique. This highly complex process manipulates fine individual yarn strands on a traditional handloom to render stunning motifs.

Kashmiri Carpets

The carpets of Kashmir are renowned for their distinctiveness, as they are handmade and hand-knotted rather than tufted. The history of carpet weaving in Kashmir dates back to the time of the famous Persian Sufi Saint, Hazrat Mir Syed Ali Hamdani, who arrived in Kashmir between 1341 and 1385 AD. Along with introducing Islam to the region, he also brought skilled craftsmen and artisans, thereby establishing the foundation for the cottage industry in Kashmir. The art of carpet weaving flourished under the patronage of kings and nobles in the region, and it continues to be a significant part of the cultural heritage of Kashmir. The exquisite craftsmanship, unique designs, and superior quality of Kashmiri carpets have earned them a distinguished reputation both nationally and internationally.

The intricately woven carpet with a density of 200 knots.The level of quality attained in both silk and wool yarn, measuring up to 900 knots per square inch, is truly exceptional.Carpets with a knot density of 18x18 or 20x20 per square inch are frequently produced in Kashmir, known for their durability and longevity.Exquisite silk rugs of varying sizes have been meticulously crafted with a knot density of 3600 knots per square inch.

However, it should be noted that these rugs are.Exemplary demonstrations of expertise primarily created for public display or showcasing in museums. Over time, the density of knots per square inch increases.The quality and longevity of the carpet increase with its size. The Kashmiri carpet is known for its high price due to its exceptional value and durability.The production process has involved significant effort and a considerable amount of time.

Shop at-https://ruralhandmade.com/productdetails/carpets-hand-knotted-wool-8-x10-eco-friendly-area-rug-7

Amritsari Carpets

In the early 19th century, when Maharaja Ranjit Singh bought Kashmir under his rule, many Kashmiri carpet and shawl weavers moved to Amritsar under his patronage.With the display of Indian handicrafts at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, carpet sales saw a boom and several British businesses established themselves in Amritsar.The skilled craftsman got the availability of fine quality wool from the neighbouring hill states which led to the creation of hand-knotted woollen carpets. In this technique, the woollen yarn is knotted (using the Persian knot technique) around the individual threads of the cotton warp, utilising the Persian techniques.

While weaving new motifs the weavers also used a colour-coded Naksha pattern that was drawn on graphs.In Rajasansi, artisans make 9x16 inch quality which is 13-16 knots per which and the quality is lower in comparison to Kashmiri carpets.The artisans of Raja Sansi gradually became experts in the craft and almost all houses in Raja Sansi had set up looms where both men and women were working equally on the craft. The 1980s was the golden age of Amritsari Galeecha and even Bhadohi and Mirzapur imported carpets from Amritsar. Until the early 1990s, carpet manufacturers and exporters were getting monetary incentives for exporting, Rs. 20 lakh incentive per Rs.1 crore of export.

Kunbi Saree

The kunbi is a double layered rudraksh saree which was created centuries ago by the Kunbi tribe. This was mainly worn by Kunbi and Gawda Community of Goa.In this word kunbi, ‘Kun’ means people or community and ‘Bi’ means seed.This saree fabric is known as ‘ Kaapad’ in their native language.Believed to be Goa's original inhabitants, the Kunbi community traditionally cultivated paddy, which the sarees pay homage to through their checkered motifs.Alternating black and red squares pattern these breezy cotton sarees, representing fertility and vigor. Sometimes blue threads substitute red to create a cooling visual contrast. The seven-yard iterations make for festive bridal drapes while everyday versions measure four yards.

True to their functional rural origins, Kunbi sarees featured practical styling elements. Sparing use of ornamental borders and minimalist pallu designs allowed free movement for long hours in the fields under the baking sun. Lengths reaching just below the knees offered the same liberating comfort.

Puan Cloth

The visually stunning handwoven Mizo puan serves as both fabric and symbol of cultural identity for Mizoram's women. Literally meaning 'cloth used to cover or wrap around the lower body', the puan traditionally comprises an integral part of local attire.

Draping styles evolved alongside the puan's functional evolution as everyday wear. An ankle or calf-length puan wraps snugly around the waist like a sarong, pairing with carefully embroidered vests or cholis. Intricate handwoven twill patterns the puan's borders, showcasing tribal geometric designs. Originally woven from hand spun cotton yarns, today acrylic wool makes for more durable and easier to maintain puans. However, traditional loin looms remain the preferred tools for creation despite options like fly shuttle looms. The convenient backstrap setup allows weavers flexibility to work from home while managing daily chores.

Through the nuanced symbolism of colors and designs, each Mizo puan relays a distinct message to the viewer. Plain black puans with embroidered hemlines communicate mourning. New mothers don elaborate red and white banded styles once permitted to leave home post-delivery. And then there are the red and black wedding puans, said to signify the bride's shift from maidenhood to marital bliss.

The puan stands testimony to how versatile humble homemade textiles can prove when passionately envisioned and executed. From rustic bamboo groves where folk tunes once set the rhythm of the loom shuttle, today international runways and boutiques beckon equally.

Panchachuli Weave

In the remote Panchachuli valley nestled in the Himalayas, a small community of displaced Tibetan families rebuilt their lives from scratch around the woollen arts. Left with meagre resources, the women turned to their ethnic weaving skills to provide for households as primary breadwinners. Soon a resilient wool crafting tradition blossomed despite the challenging terrain.

Originally Tibetan nomads, they adapted merino, pashmina and sheep wool weaving to the Indian landscape. Local Himalayan motifs merged with Tibetan patterns in these hand-spun, naturally-dyed stoles and shawls. Intricate knitting crafted sweaters, caps and mittens fending off harsh winters at altitude. Ancient vertical looms make way for ergonomic frame styles allowing flexible production from home.

Jamdani(Santipore) Saree

The quaint weaving town of Shantipur in West Bengal has crafted its place on India's handloom map over centuries through sheer endurance and excellence. Renowned as much for superfine dhotis as ornately woven jacquard saris, the Shantipur legacy continues to win global cognizance today.

Originally patronised by 18th century king Krishnachandra Rai, the humble weaving hub soon gained fame for delightfully delicate textiles befitting royalty. Traditional jacquard weave saris incorporating intricate foliage, geometric and paisley motifs remain hallmark styles, replicated but never replicated. Made from premium cotton and silk yarns, they retain a fluid grace despite dense design detailing.

The Do-Rookha technique used to create these textile marvels showcases true mastery. Translating to 'two faces', it involves patterning both sides of the saree identically through meticulous design transfer. Remarkably, the front and reverse sides bear zero distinction when these diaphanous six yards elegantly unfurl.

Shantipur’s prized dhotis and jacquards rely chiefly on fly shuttle frame looms for fruition. The nimble ‘adda’ (fly shuttle) dances rapidly across fine warp and weft threads building patterns of stunning symmetry. Achieving such precision consistently signals the deft handiwork of a seasoned master weaver.

Pashmina Shawls

High up in the rarefied air of the Himalayas, treasured herds of Changthangi and Pashmina goats develop ultra-soft underfleece to endure harsh winters. For centuries, Ladakh's nomadic Changpa tribes have shorn and hand-spun this rare wool into the prized Pashmina shawls coveted globally for their featherweight luxury.

The softness ensues from the tiny 14-19 micron fiber diameters that allow easy draping and insulation despite extreme thinness. Changpa women deploy ancient manual spinning techniques passed through generations to transform the wool into fine yarn. These then reach the loom for meticulous weaving into intricate shawls patterned with Kashmiri motifs.

Common motifs replicate the alpine flora like lotuses, chinar leaves and wild tulips the tribes live amongst. Some designs interpret avifauna from the high-altitude wetlands dotting the terrain, incorporating dancing cranes and swarming sparrows. Wedding shawls feature the kairi - a special walnut dye-based motif symbolising fertility. Such nuanced cultural symbolism underscores Pashmina's legacy beyond material utility.

As consciousness and ethics emerge as new chic, Pashmina enjoys renewed fame with designers and royalty alike. For wrapped within its gossamer folds gleam the proud legacy of indigenous communities thriving harmoniously on hostile terrain through sustainable animal husbandry and handicraft.

Shop at-https://ruralhandmade.com/productdetails/vibrant-and-unique-indian-kashmiri-stoles-1

Patola Saree

The resplendent patola silks remain an integral part of Gujarat's cultural lineage, dating back almost a thousand years. Originally worn exclusively by royalty like the Solankis, Vaghelas and later Mughals, today these double ikat sarees signal affluence and elevated aesthetics. The lengthy six-month production relies solely on three specialized Patan-based artisan families trained in guarded weaving secrets. Such exclusivity heightens the value, with certain heirloom patolas commanding prices of luxury cars now!

The uniqueness stems from the incredibly complex technique of simultaneously dyeing wrap and weft threads in pre-designed patterns before weaving named 'double ikat or badi'. Myriad hues merge in stunning play to create an entirely non-repeating motif fluidity across six resplendent yards. Figural motifs depict religious narratives while floral medallions replicate temple architecture.

Certain patolas like the rajevadi with whimsical elephants ambling amidst flowering trees required exemplary visualization in aligning motif continuity across lengths. Newer modern interpretations showcase geometric Mashru prints or bandhani-inspired phool bharat styles catering updated aesthetic sensibilities. Yet all patolas remain unified by the superior finesse of detailing crafted from years of tacit knowledge transfer.

Today, recognition through geographical indication tagging prevents imitation trading. Government infrastructure provides raw material access and avenues for new market linkups. While an important Gujarati bridal trousseau treasure, Patola saris now find patrons amongst global royalty like the British Queen and even Hollywood celebrities. The expanded patronage promises to nurture the legacy to greater heights while retaining its unmatched exclusivity and visual allure.

The handloom sector plays a significant role in the economy of a country. It offers several advantages such as the ability to adapt to small production runs, uniqueness, innovation, and the flexibility to meet export requirements. The handloom sector has great potential to contribute to export earnings. Recognizing this, the government has identified the export of handloom products as a "Thrust Area" for the overall development of the sector. Efforts are being made to explore the optimal utilisation of resources in order to boost the handloom industry and maximise its contribution to the economy.As the handloom sector is growing at a CAGR of 8.41%, the market will exhibit a steady growth rate during the forecast period (2023-2030), several government policies are there to provide logistical support, design inputs, technology upgradation, marketing support, etc.

Handloom industry contributes significantly to the economic growth of the country and plays a significant role in export earnings. The export of handloom products in FY20 from India was valued as US$ 319.02 million, whereas in FY21, it was reduced to US$ 223.19 million. The major importer of these products are the US with US$ 83.11 million trade, followed by the UK (US$ 18.99 million), Australia (US$ 10.7 million), Germany (US$ 9.94 million), and France (US$ 9.73 million). The prime handloom export centres are Panipat, Kannur, Varanasi, and Karur, where handloom products such as floor coverings, table linen, bed linen, curtains, and embroidered textile materials are produced for export markets.

The sizable Indian diaspora and rising demand for ethical fashion elsewhere support export growth.

Although volume is driven by mass market consumers, the true value is found in conscientious consumers who recognize the craft's history. Make thorough profiles of your customers on:

Experience-seeking urban youth buys handloom apparel and accessories to stand out.

Custom batches are ordered by moral businesses to produce items and uniforms in an environmentally friendly manner.

Indian customers abroad desire sarees and unique presents for celebrations or domestic purposes.

Handloom aficionados and collectors seeking unusual weaves to invest in.

For premium positioning, satisfying such specialized motives is essential.

The handloom supply chain sets itself apart by stressing ethics and fair salaries. Here's a quick rundown:

Cotton and silk yarns are the key basic elements for this natural, biodegradable fabric, and they are supplied from recognized artisan cooperatives.

Weaving Clusters: Over the years, several places have specialized in specific techniques - Varanasi for silks, Manipur for moirang phee, Assam for muga silk, and so on. Identifying artisan groups in clusters guarantees authenticity.

Spinners, Dyers, and Other Support Functions: Yarn dyeing with vegetable dyes, zari work, block printing - specialist auxiliary crafts increase the value of the product.

Processing equipment: Hand-holding export hubs include pre-shipment quality inspections, steam pressing, and specialist packing equipment.

Collaborations with experienced designers, brands, and craft NGOs help to increase commercial appeal.

For seamless handloom distribution, efficiency and awareness must coexist:

Local collecting points Picking up batches from clusters directly.

Fabric, yarn, and accessory quality control is meticulous.

Product batch, artisan origin, and quality grade inventory classification.

Gentle fabric steaming, non-toxic approved methods, and biodegradable packaging

Shipping small consignments at a low cost with integrated logistics partners

Marketing the Priceless Luxury of Heritage through the emotional resonance evoked by handloom weaving offers it an unparalleled X-factor that no mass-produced cloth can match. The historic craft story must be emphasised in brand positioning:

Highlight the origin of the handloom, the artisanal community, and the traditional techniques used.

Campaigns that bring culture and personal narratives to life - Collaboration with influencers

Catalogues and lookbooks for retail buyers that value true luxury.

Initiatives that link urban clients with weaving clusters via immersive workshops.

In essence, the supply chain in question is characterised by its localization and reliance on labour-intensive processes, primarily rooted in the traditional artisan skills found in various villages and small towns across India. This unique supply chain presents a significant challenge as it requires the preservation of these traditional skills while simultaneously modernising the infrastructure.

Indian handloom has enormous development potential, both nationally and worldwide. However, commercial success requires a significant investment in understanding the craft's ethos, expert craftspeople, and conscious consumers. This industry is known for its complexity, diversity, and resilience. And these are the elements to creating an egalitarian, ethical supply chain that combines economic expansion with historical preservation.

Recommended